Today, the Pokémon franchise is the highest-grossing media franchise of all time. With dozens of incredibly successful video games, over a thousand episodes of its iconic animated series, an even greater number of collectable Trading Cards and with characters more recognisable than Disney’s Mickey Mouse.

After nearly 25 years of Pokémania, it’s almost impossible to remember a time from before Pikachu. For many of us, Pokémon’s just always been there as a part of the pop culture landscape. For others, especially those of us who grew up with the very beginning of the franchise, it can even be life-defining. Directly shaping friendships, relationships and life experiences (all of which I can personally attest to).

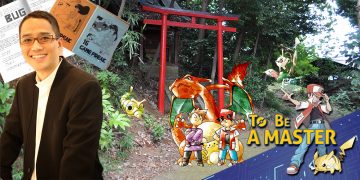

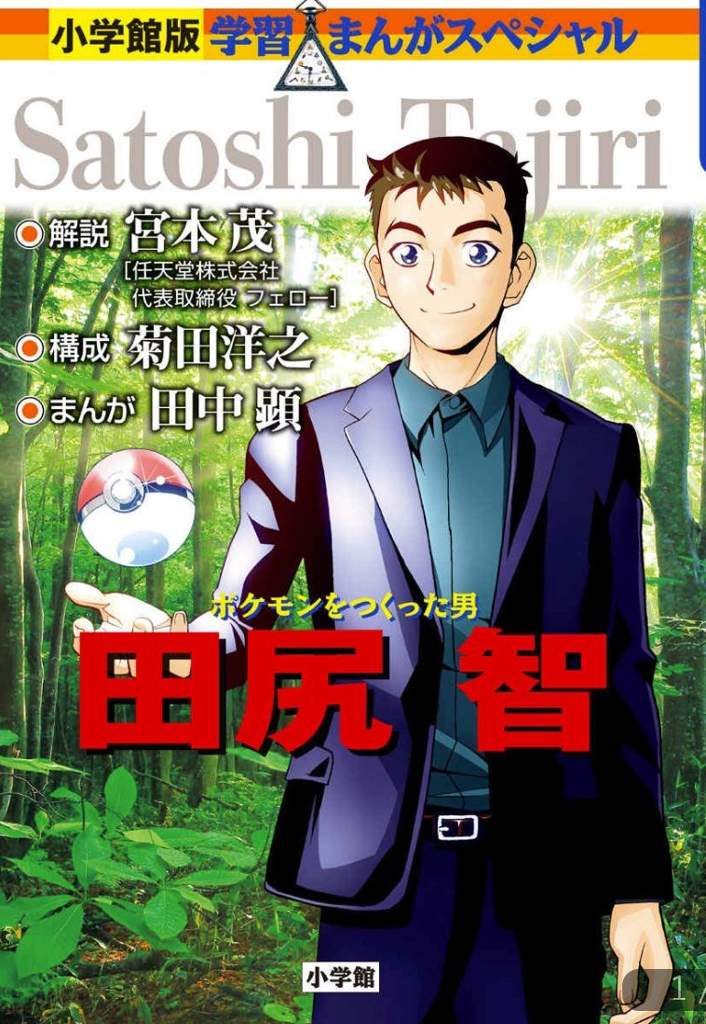

If you’re really looking for someone whose life is incontrovertibly intertwined with every single strand of the franchise’s DNA, though, look no farther than the man behind the entire thing to begin with: Satoshi Tajiri. So, where better to start this series of deep dives into the Pokémon franchise than the very, very beginning? This is the story of the man who started it all. The original PokéManiac.

Pokémon is a direct product of Tajiri’s childhood in Japan. A one-two punch of his own personal obsessions coalescing into one world-changing form.

The origin story of the dedicated Dr Bug

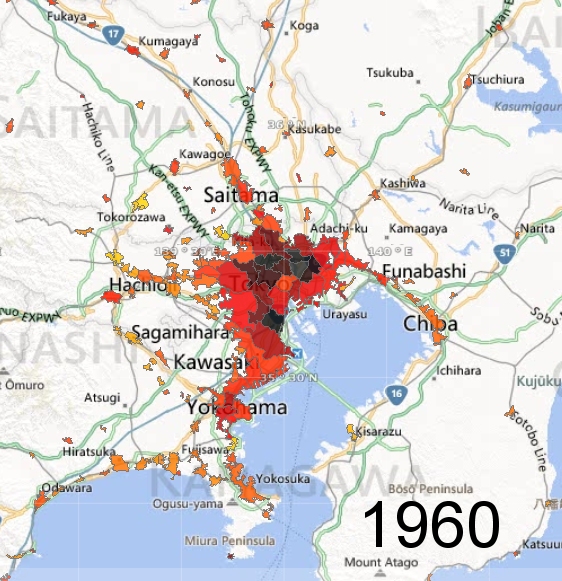

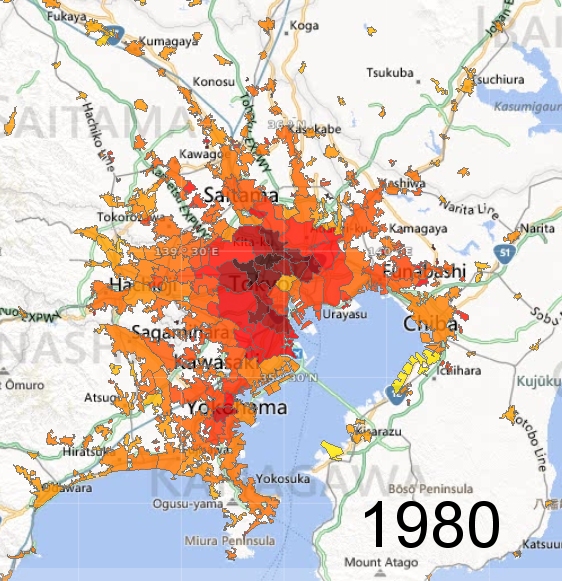

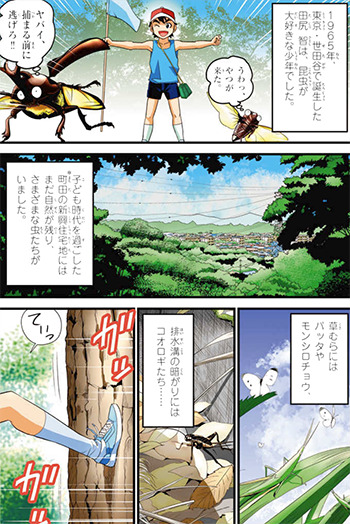

Tajiri found himself growing up through an era of significant and rapid change in the country. The area of Tokyo he lived in, Machida, was for a lot of his childhood a verdant and forested suburban world.

Within this wild environment, the young Tajiri developed the first of his significant obsessions that would directly lead to the birth of the Pokémon franchise. A deep and caring fascination for the insects he shared this area with.

“They fascinated me. For one thing, they kind of moved funny. They were odd. Every time I found a new insect, it was mysterious to me. And the more I searched for insects, the more I found. If I put my hand in the river, I would get a crayfish. If there was a stick over a hole, it would create an air bubble and I’d find insects there. I usually took them home. As I gathered more and more, I’d learn about them, like how some would feed on one another.”

Satoshi Tajiri, TIME Magazine November 1999

While catching insects such as beetles was a relatively common childhood hobby at this time in Japan, Tajiri’s obsession and keen intent to learn drove him much farther than his friends.

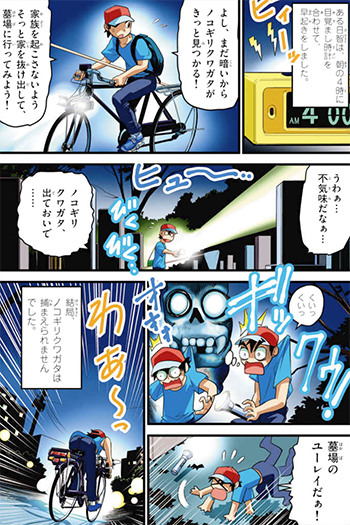

His determination to capture a Saw Tooth Stag Beetle even saw him once sneaking out of his home at 4am. These beetles were nocturnal, and he had read that they could be found at places such as the nearby cemetery. But, while he might not have had to contend with a real-life Gengar, the young Satoshi was nonetheless creeped out by the spooky setting he found himself in and returned home empty-handed and tired.

Samples of the 2018 biographical manga about Tajiri’s life

Samples of the 2018 biographical manga about Tajiri’s life

However, not to be deterred, he studied further and learned that they liked to sleep under stones during the day. So rather than joining the other kids slathering honey on tree barks to attract any awake insects, Tajiri instead had the idea to “put a stone under a tree… [and so] in the morning I’d go pick up the stone and find them”. To the astonishment of his friends, Tajiri finally succeeded in snagging a Saw Tooth as a rare prize for his growing collection.

This dedication and studied inventiveness earned Tajiri the nickname “Dr Bug” from his schoolmates. He even kept an indexed journal of his finds – his own ‘BugDex’.

Unfortunately, Dr Bug’s days were numbered. The rebuilding of the country following the devastation of World War II and rapid modernisation eventually led to the city’s expansion and the loss of this green space. One day, Tajiri was suddenly greeted with a metal fence and construction signs as he headed out to his usual woodland hunting grounds. Although he was by now becoming a teenager, he had little choice but to leave Dr Bug behind him.

The urban sprawl of post-war Tokyo as visualised by Perihele.

Years later, Tajiri cited this change as one of his inspirations for what would become Pokémon. He wanted to, in some way, allow today’s children to experience the sense of exploration and bug hunting that was such a factor of his childhood.

“Places to catch insects are rare because of urbanisation. Kids play inside their homes now, and a lot had forgotten about catching insects. So had I. When I was making games, something clicked, and I decided to make a game with that concept. “

Satoshi Tajiri, TIME Magazine November 1999

Dr Bug: The Arcade Edition

With his exploring days gone and the woods concreted over, Tajiri spent his teenage years in the arcades. Much to the chagrin of his parents, whom Tajiri once described seeing it to be “as sinful as shoplifting”. His enjoyment of games like Space Invaders quickly became Dr Bug’s new fixation. One that seemingly threatened his future as he struggled to graduate from High School as a result of skipping out of class so much.

But Tajiri wasn’t much interested in academic life anyway, despite his studious nature. Even the job his father attempted to secure for him as an electrical-utility repairman to try and keep him out of trouble was not to his liking, so he turned it down. He did eventually graduate high school – thanks to taking some additional make-up classes – but chose only to follow it up with a two-year course at Tokyo’s National College of Technology studying computer science and electronics.

Even this course merely fed into his now single-minded focus on gaming. He’d even spent so much time in one arcade, and its owner had come to know him so well, he received a to-be-decommissioned Space Invaders machine to take home with him.

But, not content with merely playing the games, Tajiri had also started to write about them too. In 1983, at 17, he and a few of his friends began writing and self-publishing a gaming fanzine focused on sharing tips for the games he was playing at the arcades.

The name he gave this fanzine was merely a reference to his own fanatical approach to the video games made by legends such as Taito’s Tomohiro Nishikado or Namco’s Toru Iwatani, the creators of Space Invaders and Pac-Man respectively. But, little could he have realised that Game Freak would one day stand alongside his own name in the industry’s history books and even far exceed his heroes’ achievements.

The rise and rise of Game Freak

As far as fanzines go, Game Freak was a moderate success. The magazine would eventually move on from being hand-written and scanned to being more professionally printed. More contributors would also eventually come onto the project. Of all his friends and Game Freak contributors, though, it’s Ken Sugimori who stands out today.

Sugimori was Game Freak’s illustrator, drawing the cover art as well as incidental images throughout the magazine. As the eventual lead artist on the Pokémon series, though, Sugimori can be directly credited with the creation of the vast majority of the original 151 Pokémon – as well as dozens more since. He discovered the Game Freak magazine early in its life, writing to Tajiri as a fan and asking to get involved as an artist for it.

Through his time working on the Game Freak magazine, Tajiri came to learn not only about how to beat the games he was writing about, but also the beginnings of knowing how they were made in the first place. He may not have been Dr Bug any more, but he was undoubtedly once again starting to feel that same pull as the elusive Saw Tooth had on him.

That drive for knowledge, and to put it to practical use to compete against his peers, resurfaced in Tajiri. Plenty of the games he was playing, he thought, could have been made better. So he simply set out to do so.

Game Freak turned Game Maker

Having won 200,000 Yen in a competition run by SEGA for people to submit game design ideas back when he was 16, this was not even Tajiri’s first foray into the world of making games, rather than playing them. Perhaps inspired and driven by memories of that win, he set to work.

To begin with, he simply acquired and then proceeded to take apart a Nintendo Famicom system. You could learn a lot about early consoles by merely investigating the system’s chips, but, without costly official development kits, it was also the only way to hack the system to run their own code. Then the real work began in the two years Tajiri spent learning the Famicom’s Family BASIC programming language.

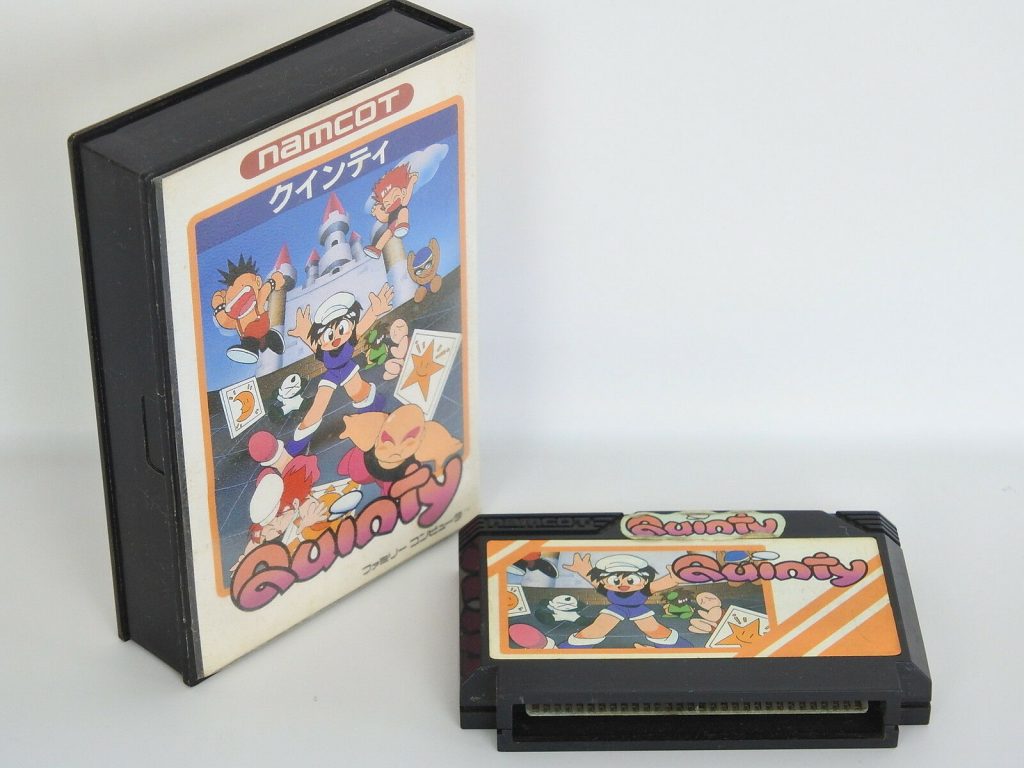

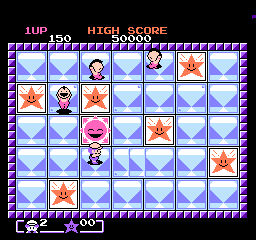

By 1989, Game Freak had morphed from being a fan-made magazine about video games into making them. Some of the existing Game Freak team joined Tajiri and Sugimori in their new game development scheme, but they were lacking the ability to make music for their games. Junichi Masuda, studying at the same technical college at the time and a keen musician, joined the team and together they created Quinty. A puzzle game where the player – on a mission to save their girlfriend – must flip tiles on a grid to defeat their enemies.

But just having made a game was no good. The group wanted their game out there, and so they needed a publisher. As fans of Namco’s games from the arcades, the team were keen to partner with them, but the company refused to contract them as individuals. Thus, Tajiri, Sugimori and Masuda officially founded Game Freak Inc. in 1989, and Namco published Quinty onto the Nintendo Famicom the same year.

Over the next five years, Game Freak went on to develop six more games for both SEGA and Nintendo’s platforms.

Unusually for such a small and inexperienced team, Game Freak was all but immediately thrust into working on games starring Nintendo’s biggest names.

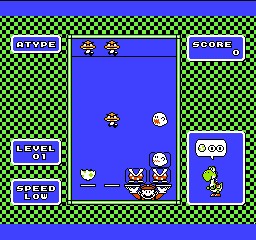

Yoshi was a puzzle game as basic as its name (though it also went by the names Yoshi’s Egg in Japan and Mario & Yoshi in Europe), tasking players with sliding four vertical stacks around to trap enemies within both halves of Yoshi eggshell.

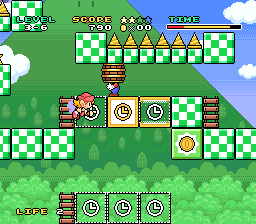

Mario & Wario, meanwhile, was an unconventional platform game designed around the NES’ mouse accessory. Controlling a fairy like a cursor to guide Mario through each stage, rather than simply running and jumping as the plumber himself.

While both titles were still very much small-in-scope spin-off games, it was still shocking that Game Freak – a handful of young men making games for the first time – were working so closely with Nintendo already.

Yoshi / Mario & Yoshi / Yoshi’s Egg

Mario & Wario

The reason for this close and trusting partnership with Nintendo? It all comes down to one fateful – and successful – pitch meeting at Nintendo’s offices in 1990. The team presented Tajiri’s idea for his second game in the hopes that Nintendo might find interest in the concept they’d cooked up. Unlike the licensed titles Game Freak would spend the first half of the 90s actually working on to bring in money and pay the bills, this was a game very close to Tajiri’s own heart. One born of his own experiences and inspirations as a child.

That game, of course, was Capsule Monsters – or as it would eventually come to be much better known by, Pokémon.

Next week: The full story of the six-year-long development of Pokémon Red & Green. The history of the original Godzilla-inspired Capsule Monsters pitch and the struggle to make the very first Pokémon games a reality – almost prematurely ending the fledgeling Game Freak studio.

Or… you can read it today by joining us on Patreon!