As we learned in the first part of this series, Satoshi Tajiri – Pokémon’s creator – was a man for whom passion became an obsession. His childhood exploring the woods near his home in Machida, Tokyo, earned him the nickname “Dr Bug”. His later fixation on video games eventually grew into poring over them and writing detailed guides for other players. Not to mention threatening his future by nearly causing him to drop out of school.

However, we wouldn’t be here, talking about him, today were it not for his obsessive traits. His love of video games developed into the frustration that, surely, they could be even better? As all great obsessives are won’t to do, Tajiri set about solving this problem quite directly. If the games he was playing weren’t that great, he’d just make his own, better games.

Joined by Ken Sugimori and Junichi Masuda, his small indie development studio, Game Freak, had begun to make a name for itself. Multiple collaborations with Nintendo on games starring its most prominent heroes, like Mario, Yoshi and Wario, had effectively become Game Freak’s bread and butter throughout the 90s.

But, throughout all this time, Game Freak had been quietly working on an idea much more significant in scope than the puzzle and platformer titles they’d mostly worked on so far. Inspired by a heady mix of influences straight out of Tajiri’s childhood – the Godzilla films, Ultraman and his days as “Dr Bug” – Capsule Monsters was the focus of the team’s most special efforts.

The birth of Capsule Monsters

With the release of Quinty onto the Nintendo Famicom in 1989, Tajiri and his Game Freak cohorts were now, officially, video game developers. Next, they merely needed to come up with an idea for another game.

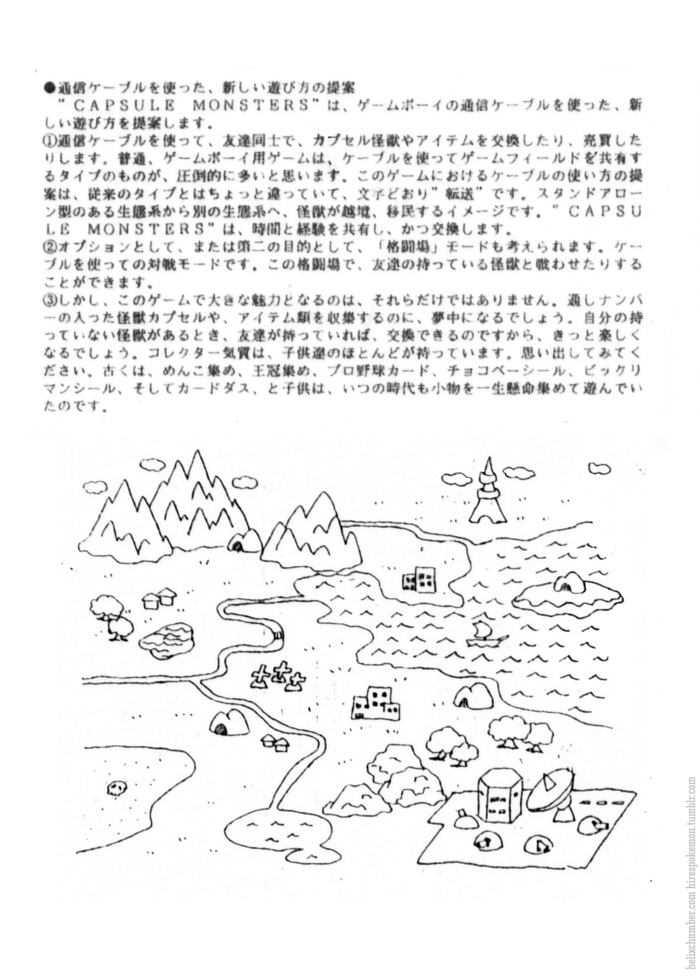

That same year, Nintendo had released the Game Boy. Players could now take their favourite games with them, beyond the home, for the first time. Seeing kids playing Tetris together on their Game Boys, connected via a Link Cable, was a significant inspiration for Tajiri as he contemplated his next game.

“The communication aspect of Game Boy. It was a profound image to me. It has a communication cable. In Tetris, its first game, the cable transmitted information about moving blocks. That cable really got me interested. I thought of actual living organisms moving back and forth across the cable.”

Satoshi Tajiri, TIME Magazine November 1999

The idea of insects “crawling” through the Link Cable between the two systems lighted a spark within Tajiri’s mind that linked his imagination to his memories of being Dr Bug as a child. He was acutely aware, thinking back upon the chainlink fences and concrete mixers that took over the forests of his childhood, that there would be no more Dr Bugs today. Perhaps, instead, he could recreate the same experiences as a video game?

So inspired was Tajiri that he worked on developing the idea restlessly. Pulling all-nighters to come up with an idea that could both accurately represent his childhood memories and be fantastical enough to interest modern kids.

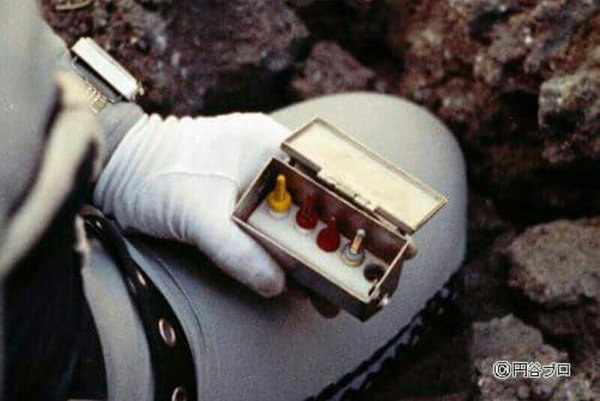

To expand the scope beyond merely ordinary insects and tadpoles, he had the idea of finding and collecting monsters – especially Godzilla-inspired Kaiju, instead. A recent series of Ultraman – UltraSeven – had centred around a very similar concept and also solved one major stumbling block for him: “Where would you keep a 10-foot tall pet monster?”.

“UltraSeven” kept its monsters in these capsules in between fights

The Ultraman series is one of Japan’s most popular long-running ‘Power Rangers’-style shows

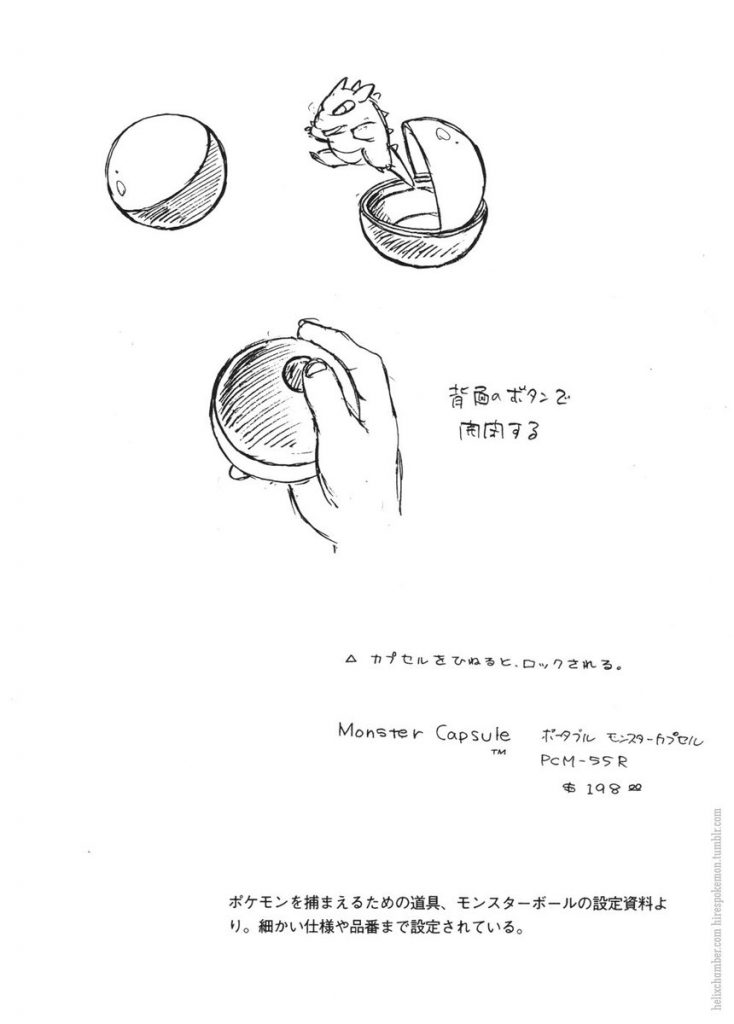

Ultraman solved this problem by storing their monsters in small, pocket-sized capsules, perhaps inspired themselves by similar technology within the pages of Akira Toriyama’s hit Dragon Ball manga. It was a solution Tajiri was happy to crib almost wholesale, reworking it to also fit along the lines of the “gashapon” blind-buy capsule toys often found outside high street stores. The name would come much later, but this was the invention of the iconic PokéBalls as we know them today.

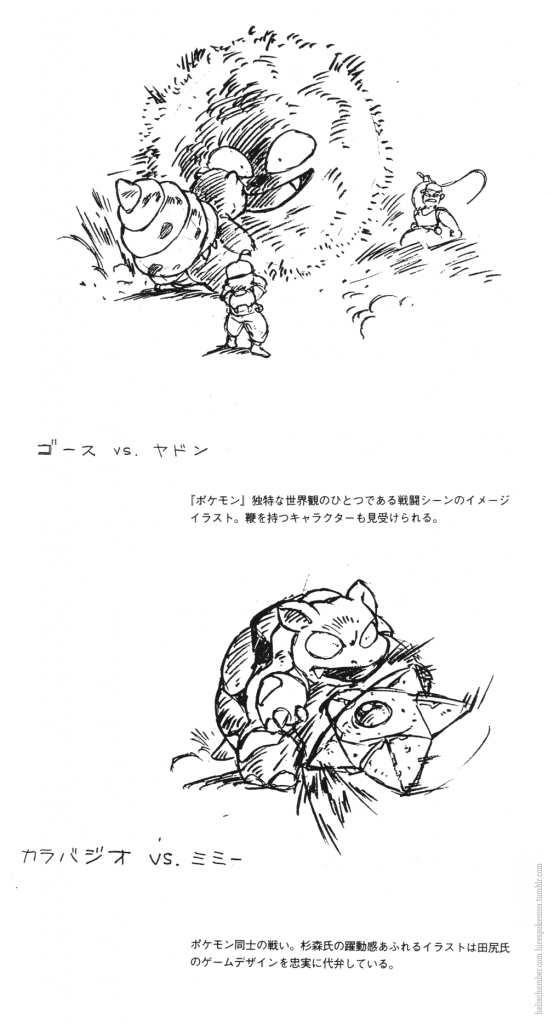

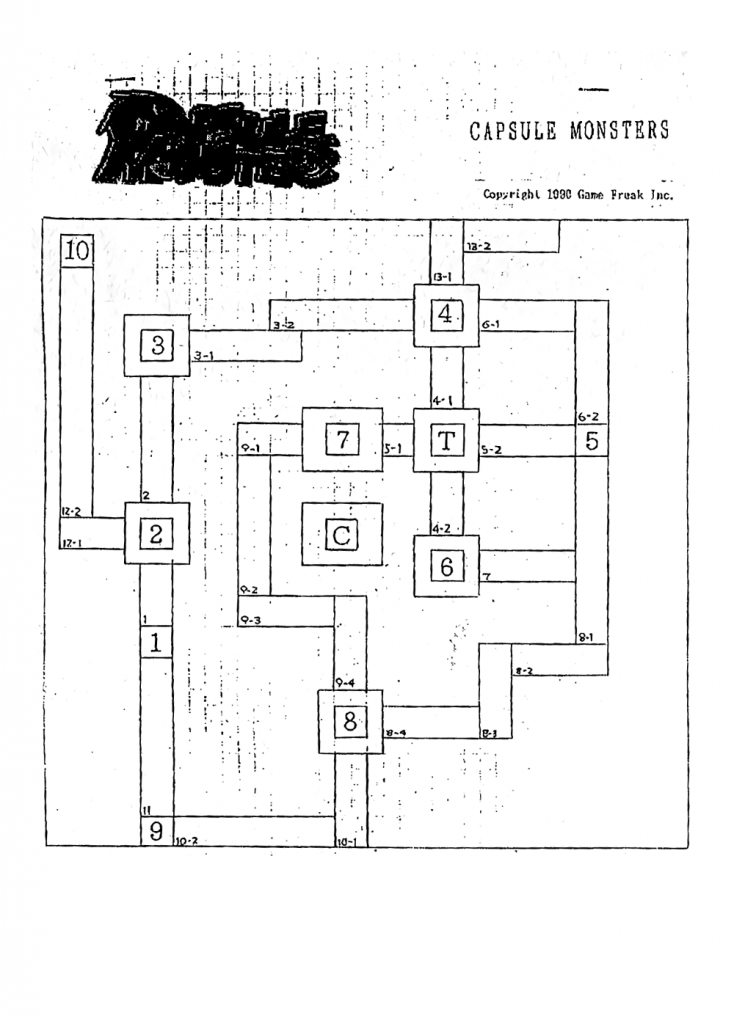

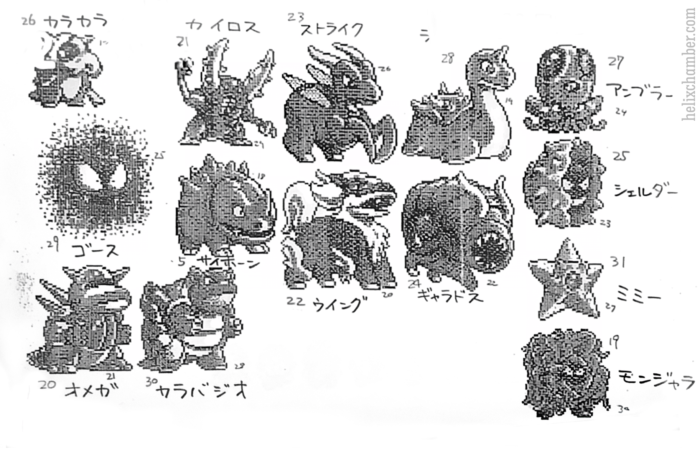

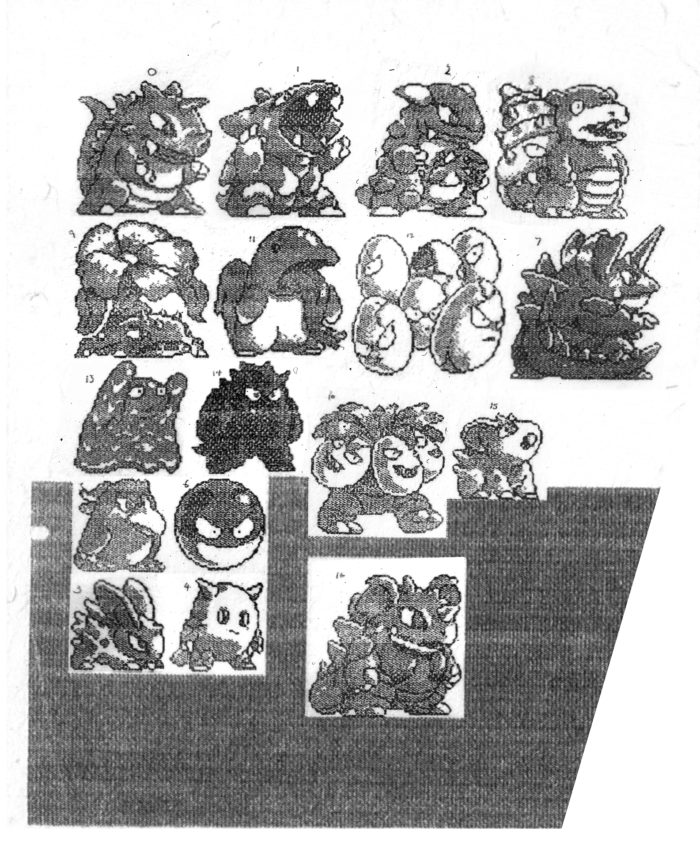

In 1990, a Capsule Monsters pitch document was born. Illustrated by Ken Sugimori and written by Tajiri, this was a hefty book filled with dozens of pages of story details, concept art, maps, prototypes of the game’s core battle feature and examples of the “200” Capsule Monster designs planned for the game.

Sampling of the Capsule Monsters pitch document in high quality courtesy of HelixChamber.com

The scope of the game – especially for such a small and inexperienced team – meant that Game Freak couldn’t simply make it and shop for a publisher afterwards, as they had done for Quinty.

The now-President of The Pokémon Company, Tsunekazu Ishihara – at the time part of Ape Inc., the developers behind games like Earthbound – had helped Game Freak with some of the business elements of the Quinty deal with Namco. So, naturally, Tajiri brought the pitch to him first of all.

Ishihara was so blown away by the concept he immediately arranged a meeting with Nintendo. The late Satoru Iwata, also working with Ishihara at Ape Inc. at the time, joined the two in an unorthodox meeting with Shigeru Miyamoto. Even in 1990, Nintendo was the dominant force in the games industry. Receiving a pitch from a small team of independent developers in their early 20s with a single release to their name was unheard of – it still mostly would be today.

But, the pitch was a total success, and Nintendo signed Game Freak on to make Capsule Monsters exclusively for the Game Boy. Miyamoto downplays the impact he had on the series beyond this, but Tajiri himself came to view the veteran developer as a mentor and a high tidemark of what he’d like to achieve.

In the eventual development of the Pokémon anime, the protagonist and his rival were originally named Satoshi and Shigeru in respect to this relationship the two men developed.

Tajiri: I really look up to Miyamoto-san. In the TV series, Shigeru is Satoshi’s master. In the game, they are rivals. Shigeru is always a little bit ahead of Satoshi.

Satoshi Tajiri, TIME Magazine November 1999

TIME: Does Satoshi ever catch up with Shigeru?

Tajiri: No! Never!

TIME: Have you caught up with Miyamoto-san?

Tajiri: I think very highly of him. I’d memorize each piece of advice he gave.

The work begins

With Nintendo’s backing, the team at Game Freak set to work hammering out the details from the pitch document into actual game mechanics. Tajiri knew that trading the Capsule Monsters had to be a vital component of the game – especially since it was a headline attraction for both Ishihara and Miyamoto – but they initially struggled to make it fit within the game’s design.

Settling on an extensive trading animation where players would have to say “goodbye” to the monsters they were trading, the team began to strike upon a rich vein that ultimately would make Pokémon such a massive success.

They were determined to introduce the illusion that the Capsule Monsters were living creatures within the Game Boy, rather than merely data. To achieve this, Sugimori argued for a need to balance giant, aggressive Kaiju-style monsters with cute and endearing ones.

These discussions ultimately paved the way for the series’ iconic evolution mechanic. Not only could players ingratiate themselves upon smaller, cuter monsters early on, but by being directly responsible for their growth into behemoths such as from Charmander to Charizard, players would be directly attached to them too. When trading them with other players, it would be a big deal.

All that the team now needed was the final piece of the puzzle: what would drive players to do these trades? The answer to this question is perhaps one of Miyamoto’s most significant personal influences on the direction of the franchise. A decision that only a man signing off the costs of the game’s production could make. They would ‘simply’ make two games, rather than the one.

“At first, there were no plans for the different Red/Blue carts—it was going to just be a single cart, but I wanted to do something a little more creative for this. Since the core of the game was catching and trading Pokémon, creating two different cart versions which had slightly different chances for each pokémon to appear would encourage and necessitate friends to trade with each other, and make the whole experience more fun.”

Shigeru Miyamoto / Game Maestro Vol. 4 May 2001

Crisis hits: Would this be the end of Pokémon?

For weeks, Game Freak continued working away at the initial development of Capsule Monsters. The work was going well, but it was becoming plainly evident that it was going to take a lot longer to make this game than the single year it took to make Quinty.

It wasn’t long before Game Freak’s balance sheets began to cause some concern. To fill the shortfall, Tajiri briefly returned to the publishing world, releasing several magazines and books, including “Catch The Packland – Stories of video games from Youth“, a collection of short stories relating to his teenage years in the arcades.

Meanwhile, Game Freak took on other development projects – several for Nintendo – to help pay the bills. All the while, development on Capsule Monsters continued in the background in fits and starts.

Developing and releasing six games over five years – alongside the continued development of Capsule Monsters – was taking its toll on Game Freak’s staff, though. A few years into this gruelling effort, all three of Game Freak’s programmers quit the company, complaining of the workload.

Having to replace all of the company’s programming staff to deliver on existing commitments for games such as Mario & Wario and Pulseman was a significant concern all on its own. But it was nearly a fatal blow for the Capsule Monsters project.

Development on the game had already all-but stalled in the face of the rest of the company’s workload. In 1993, with the game no closer to being ready for release, and now having lost all the programmers who had worked on it to that point, thoughts were shifting to scrap the game entirely.

From the outset, though, the entire team at Game Freak had viewed Capsule Monsters as their own passion project. People had put their free time into it, around other projects, because they believed in the game. Placing the decision on the game’s future to a vote, 80% of the staff were in favour of finishing the game.

But the problem remained that three years of on/off development work was now rendered useless. Bringing in new developers to work on the existing code with no handover would be difficult, time-consuming and expensive.

Luckily for both the team and for Pokémon’s continued future, not only had co-founder Junichi Masuda been studying programming in his own time, but it was the Capsule Monsters codebase itself that he had been using as a reference.

Volunteering to take over as the lead programmer, as well as the game’s composer, his fortunate ability to step in rescued the floundering Capsule Monsters development. Thanks to Masuda, the crisis was averted, and the once-uncertain fate of Pokémon was saved for another day.

However, the rest of the game’s development was still far from smooth sailing. A year later, a computer crash nearly doomed the entire project all over again. Under the threat of losing literally everything done so far on the project, it was once again up to Masuda to desperately try and find the solution.

“Somewhere midway through the development, maybe in the fourth year or so, we had a really bad crash that we couldn’t, we didn’t know how to recover the computer from. That had all of the data for the game, all of the Pokémon, the main character and everything. It really felt like, “Oh my God, if we can’t recover this data, we’re finished here.” I just remember doing a lot of different research. I called the company that I used to work for, seeing if they had any advice to recover the data.

I would go on this internet service provider back then called Nifty Serve. It’s like a Japanese version of CompuServe. I’d go on and ask people that I never talked to for advice on how to recover the data. I would look at these English books about the machine itself, because there wasn’t a lot of information in Japanese, just to figure it out. We eventually figured out how to recover it, but that was like the most nerve-wracking moment, I think, in development.”

Junichi Masuda, interview with Polygon 2018

The last and lost Pokémon

Meanwhile, the plans to include 200 Capsule Monsters in the game were also hitting a brick wall. The limitations of the Game Boy cartridge were becoming a significant hurdle for the expanding scope of the game. Once again, Miyamoto stepped in to save the day by throwing Nintendo’s money at the problem.

“The one bit of support I did give to the Pokémon project was convincing Nintendo to increase the size of the backup memory for the cart. […] With that addition, we were able to include the full 151 pokémon to catch—gotta catch ’em all!”

Shigeru Miyamoto / Game Maestro Vol. 4 May 2001

The number of monsters still had to be cut down to fit into the 1MB of memory they now had available, but eventually, the final roster of 150 Pokémon was settled on.

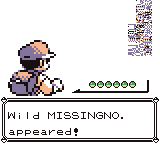

This culling of monsters to make space even had an unusual impact on the history of the Pokémon franchise itself.

While the burdensome data was removed from the game, the internal index of all the Pokémon originally programmed in was left intact. Performing a now-iconic sequence of events in the game would convince it to attempt to load the Pokémon data for one of these lost monsters. But, since the data for that given index number was missing, a “MissingNo.” error would appear, creating possibly the most infamous gaming glitch of all time.

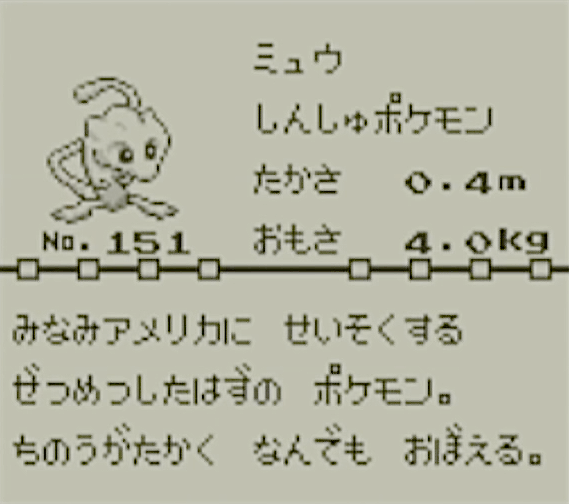

By the time the game’s development was completed, and various debug features were removed from the final game’s code, a minuscule 300 bytes of free space remained on the cartridge. This allowed just enough space for one last Pokémon to make the cut: Mew.

The game’s battle mechanics designer, Shigeki Morimoto, who had designed the Pokémon and later assisted with some of the programming, snuck the character in at the last moment. Even though, following testing, the game’s code was supposed to have been final and ready for printing without modification.

Adding Mew had exactly the effect Nintendo were hoping to avoid by the game’s code being changed after testing. Despite not being programmed to be accessible, players were eventually able to find it through bugs introduced when adding the final Pokémon.

By October 1995, following a name change from Capsule Monsters to avoid trademark issues, Pocket Monsters Red and Pocket Monsters Green were finally ready for release.

Unfortunately, while Game Freak might have finally been ready, Nintendo was not. To fit the games into their release schedule, they were pushed back several more months into February of 1996.

This extended period of development posed one final threat to the game’s potential success. By 1996, the Game Boy was seven years old – a lifetime in gaming hardware terms. Ishihara once commented that they were concerned they might have “missed the last train” in terms of interest in games for the ageing monochrome platform.

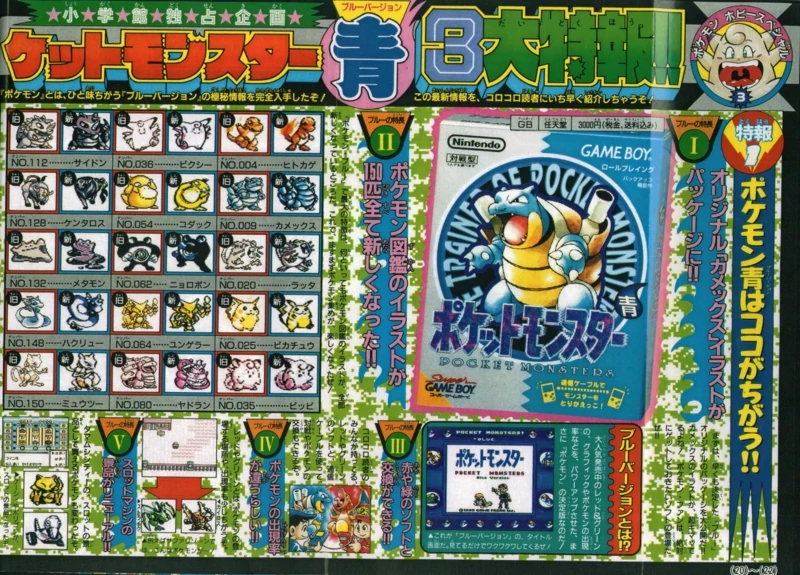

In the end, though, that late lunge may just have been the key to Pocket Monsters‘ success. The Game Boy’s ubiquitousness allowed the games to sell over a million units during 1996. Through word of mouth and extensive coverage in the popular CoroCoro magazine, the games built up from a slow start into the beginning of a phenomenon.

Pokémon Red and Blue as we got them are based on this version.

Despite several, near-terminal setbacks throughout half-a-decade, Tajiri’s Capsule Monsters dream had finally become a reality. And yet, despite all it took to get to this point, it’s just where the story really begins.

With countless games, TV shows, movies, toys, books and much more even besides, there are a lot more stories to tell about the history of the world’s most successful multimedia franchise and the people behind it.