This week saw the announcement of the latest in the on-going ‘craze’ of “miniature” versions of classic consoles: The Game Gear Micro. If nothing else, it surely lives up to the name. Launching in four colour variants, with four different games loaded onto each, the devices cost about $50 apiece. But all of that is kind of irrelevant, as the 8cm wide ‘console’ comes with just a 1.15-inch display, making it surely unplayable for anyone with hands larger than a two-year-old’s.

As a trinket to celebrate Sega’s 60th birthday, it can maybe just be seen as an amusing joke. Much like the full miniature set of plastic add-ons for the Mega Drive Mini released alongside it in limited numbers last year.

A knowing nod to the absurdity of the era itself, perhaps? After all, the Game Gear Micro does still come with an option to feed it AA batteries, to wastefully replicate the experience of the original’s voracious appetite for them.

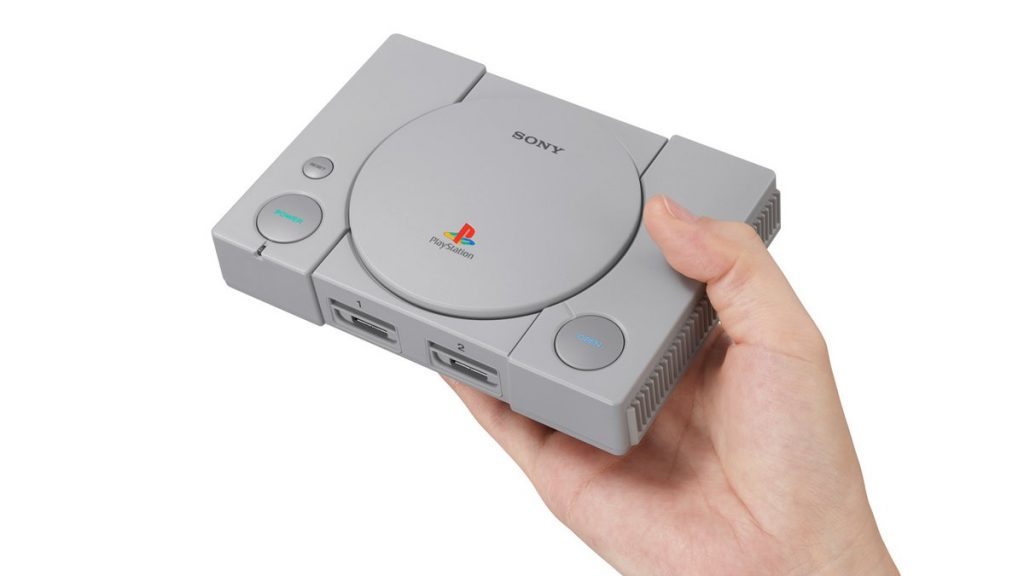

But, it shouldn’t be a joke. The appetite for all of these miniature ‘consoles’ is clear. Most have gone down well, and most have obviously sold well enough for there to be even more of them still coming. But they’re all quite meagre efforts at actually respecting the original hardware or the games of the era. Underneath the high-quality presentation, these ‘mini’ devices aren’t fundamentally different from running Raspberry Pis with Retroarch installed. Which just makes it all the more disappointing when the emulation they then rely on isn’t actually that great.

Meanwhile, an enthusiast market is booming by offering exactly what Nintendon’t, or Sega, or Sony, or – in fact, absolutely any of the actual console manufacturers. While there are other unofficial emulator-led devices such as the Evercade or Polymega coming on to the scene, FPGA is the real buzzword of the moment.

Standing for ‘Field-programmable gate array’ it essentially means that certain logic statements – or ‘gates’ – (effectively “if something is true, do this, otherwise, do something else”) are programmed on a hardware level, rather than a software level. In standard use-cases, the main benefit is primarily speeding up development processes. For gaming, however, it’s a revolutionary way to not just emulate old consoles, but to practically recreate them.

Analogue has become the leading name in the field of recreating classic consoles thanks in large part to their Electrical Engineer, Kevin Horton’s work in reverse-engineering FPGA circuits for their NES, SNES and Mega Drive ‘clones’. By using FPGA, these devices effectively act the same as the original hardware did. Performing the same instructions in the same way as the specialised, proprietary chips that dotted their motherboards.

Because you can use the actual, original game cartridges on these consoles, and because they act, with such high fidelity, like the original hardware, they’ve been a God-send not only for being able to play these games using today’s audio/visual hardware but also for preserving and renewing the life of the games themselves.

But, while Analogue can freely create hardware capable of running classic games, they’re unable to create and sell new copies of those games to run on them. This leaves only two options for most players: scour eBay for potentially highly-priced second-hand cartridges amongst a steadily declining functional stock, or jailbreak it and load it up with illegally downloaded ROMs.

The industry’s persistent war on ROMs is possibly the greatest highlight of how badly all video game publishers – but especially the platform owners – are failing in preserving and respecting their own history. The reality is that the large archives of ROMs that these companies constantly try to whack-a-mole off the face of the Internet are also the only real archives this industry has of this legacy.

Within these ROM collections, thousands of games across multiple platforms are preserved in a non-degrading digital format so that people can still play and enjoy them and that they are not lost forever. Meanwhile, the majority of copyright-owners themselves have deleted buildable source code, abandoned development materials and – often at best – have a storage unit or two where they’ve dumped old documents and cartridges in what amounts to little more than an expensive, proprietary landfill with blue shutters.

It shouldn’t be up to individuals making and sharing ROMs in increasingly dark corners to preserve these games. Nor should it be up to companies like Analogue to have to provide the modern, reliable hardware as a viable alternative to what are now practically museum-pieces in the fully-functional, well-treated original hardware.

Instead of taking the piss out of their own legacy, Sega could – and I would full-throatedly argue, should – be offering up their own FPGA solutions to being able to play their own content in a way that respects and maintains their history. All of the platform holders should.

Backwards compatibility is a big talking point at this stage of the Next-Generation hype train, partially because of Microsoft’s significant commitments to it. But, while the dream of full backwards compatibility for the modern era of disc-format and digitally distributed games is (relatively) simple enough for Xbox – a format that’s only ever existed within that era – the rest of the industry needs to do a lot better than the current occasional re-releases of ROMs packaged into an, often-times disappointing, emulator.

Between the official ‘Mini’ devices, similar-but-unofficial emulator devices such as the Evercade or Polymega, and the FPGA consoles, it’s clear that people are willing to spend quite a wide variety of prices to be able to experience these games in a more authentic way. It’d never be a fraction of the size of the main console market, but there’s no question that official FPGA devices – ones that could be manufactured at scale and sold on the high-street – would expand well beyond the enthusiast market.

Of course, it’s 2020, so an online store to download content would have to be the primary delivery system over new physical cartridges. But hey, in limited quantities at least, why not both?

There’s also very little reason why new games couldn’t also be developed for these platforms, once the hardware itself had official support once again. After all, several independent teams are still making games exclusively for platforms like the Mega Drive.

A collection of 30 ROMs, even one packaged into a neat plastic shell that looks like the original console, only ever ultimately makes the games themselves feel cheap and disposable. Perhaps having to buy an actual cartridge (or at least just knowing that it’s the alternative to downloading it) and playing the game on an actual, dedicated console can help restore a lot of that value back to these games, too.

But this is honestly just the tip of the iceberg in how badly the industry is failing at preserving its own history. Again, it currently falls to enthusiasts and independent organisations such as the Centre For Computing History. Instead of keeping all their history locked away in vaults and dusty filing cabinets, companies like Nintendo and Sega should be opening them up, cataloguing and proudly displaying it. None of what we currently enjoy would be here without all of what came before.

That history isn’t a joke. Which is what makes it so disappointing that in celebrating the act of having (just about) scraped by to survive 60 years in business, that’s all that Sega currently seems to see it as.